… Francesca Beddie visits Trier

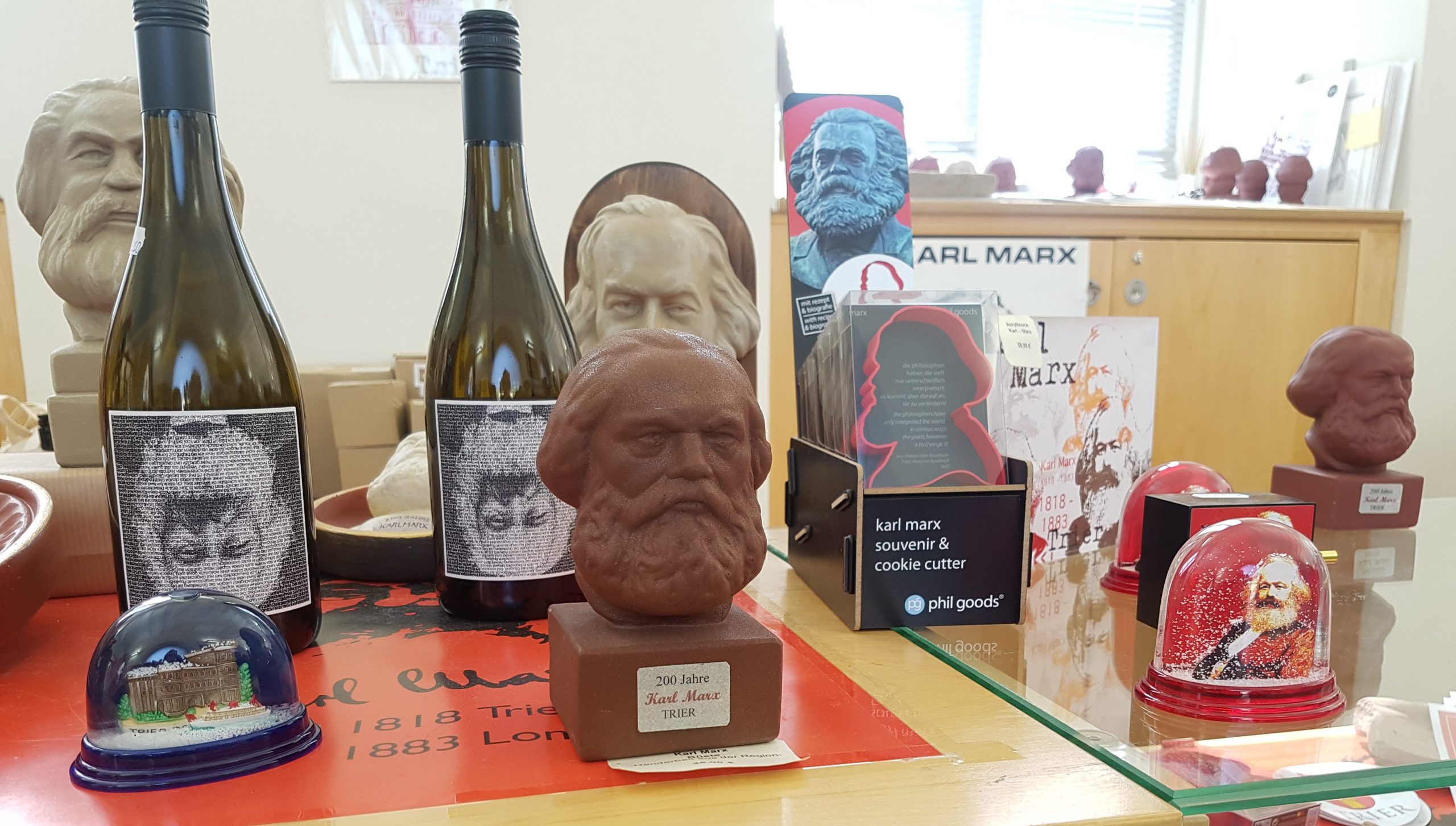

The bicentenary of Karl Marx’s birth is being celebrated with gusto in the town where he was born on 5 May 1818. Trier is festooned with his portrait, the one taken in 1875 of the white haired, woolly bearded man we have come to know as the father of communism. When you cross the road, the pedestrian light uses that same image of the mature Karl Marx. You can buy Karl Marx cookie cutters and bicycle bells, postcards and snow domes, and you can go to several exhibitions that explain his life and philosophy.

At the city museum, Stages in a lifetime sets out to ‘avoid eulogy or denunciation’ of Marx; instead, it ‘sets out to paint as true a picture as possible of the man himself’. It uses contemporary documents and paintings to trace Marx’s life from childhood and youth in Trier, to his university years in Bonn and Berlin, his journalistic forays and periods of exile in France, his other travels for pleasure and business (including to relatives from whom he pleaded financial support), and finally to being an émigré in London, where he died in 1883.

The exhibition starts not in 1818 nor with Marx but with data collected in the 1830s by the Prussian authorities to better understand the causes of poverty and ill-health in Trier. Seventy per cent of the town’s population was deemed poor or very poor. The interactive display allows the visitor to examine individual records of those designated as paupers, giving their addresses, age, working status, moral standing and family composition. Anna Mueller, 42, lived in Brittanien Street. She was classified as very poor, seen by the authorities as capable of work but ‘slatternly and depraved’. This would have influenced their decision not to give her alms. Peter Conterbach and his wife had six children. They were both said to be alcohol dependent. Their cramped, unhygienic living conditions made them particularly vulnerable to cholera. What the authorities did about this is not recorded. The Voltmar family faced the looming threat of having to pawn their belongings; Johann Zimmer was homeless with a small child. And so it goes on for 627 families. What a data set! And what a fascinating way to set the scene of the city where the young Marx grew into early adulthood!

Each of the subsequent rooms presents a mixture of paintings and documents arranged according to Marx’s circle of family, friends, teachers and colleagues. Jenny von Westphalen, his wife, also from Trier, features strongly throughout, as does Friedrich Engels, whom Marx met in 1842. In his letters, Marx addressed his friend ‘Dear Fred’ but continued in German.

As well as the poverty in cities being transformed by industrialisation, the exhibition reveals how Marx became sceptical about religion. His father, the son of a Rabbi, converted to Protestantism not out of faith but to protect his legal practice so that he could continue to provide for his family. This must have been in Marx’s mind when studying in Berlin he encountered Ludwig Feuerbach’s arguments about the idea of God as a human invention.

In one room hang two pictures of grieving parents. The audio guide describes these in detail before extrapolating their significance: the high incidence of infant mortality in the nineteenth century. We learn that, like so many, the Marx family was affected by high rates of infant mortality, losing four of their seven children. A voice reads from a letter written by Jenny describing the heartbreak of watching her eight-year-old son die.

All this material makes the visitor’s head spin with the same influences that Marx and Engels transformed into an analysis of capitalism and arguments for change. Volumes of The Communist Manifesto in German, ‘plain English’ and Braille are there to be thumbed through.

In the last room, the centrepiece is different: it is an oversize metal trunk standing open. Visitors can open the draws to see the artefacts of travel, then and now. Marx, a political refugee, was forced to move around Europe. He renounced his Prussian citizenship, rendering himself stateless. But he moved with his belongings, including furniture and books. The bottom drawer in the trunk contains a mobile phone, along with commentary that this represents the modern refugee’s most prized possession and one of the few they are able to carry with them.

The curators have been careful, perhaps too much so, to offer an answer to the question this bicentenary has posed: what is the relevance of Marx today? Instead, the exhibition ends disappointingly, with a series of pictures of those who followed the Marxist creed around the world over the short century of 20th century: Lenin, Stalin, Castro, and also Social Democrats like Willy Brandt. I don’t recall seeing Mao among the faces. He was probably there. Certainly, the Chinese have embraced the celebrations. It is they who donated the new 5.5 metre statue of Marx, unveiled at the 5 May bicentenary celebrations.

The Trier city council voted last year to accept the statue by Chinese artist Wu Weishan but added a resolution to their approval that cited the importance of observing human rights. The Mayor conceded that the decision was influenced by the fact that around 150,000 Chinese tourists visit Trier every year.