…Lisa Murray’s launch speech (17 June 2015)…

Fractured Families: Life on the margins in colonial New South Wales by Tanya Evans was supported through the City of Sydney Council’s History Publication Sponsorship Program. Over the years, the program has helped authors and publishers bring to the public over a dozen books about Sydney’s history. Through such books, the City supports lifelong learning and enables researchers, like Tanya’s family history collaborators, to find out more about Sydney’s past and to have a greater appreciation for our communities today.

I was extremely pleased to recommend support for this book because of Tanya’s commitment to public history and also for her interest in using and ‘crowdsourcing’ family history. This is a topic about which I am also passionate. Through my work as the City Historian, as a board member of the Dictionary of Sydney and a former board member of the Society of Australian Genealogists, and as a current personal member of both the SAG and the Royal Australian Historical Society, I am acutely aware of the intersection and benefits of connecting family history with Sydney’s urban and community histories.

Fractured Families is an ambitious book. It has dual aims:

- first, and foremost, it is a history of the marginalised and impoverished in colonial NSW – highlighting the difficulties faced by the aged poor, mixed relationships, abandoned women, orphans and spinsters.

- and secondly, it examines the methodologies and motivations of public history and family history.

These are weighty, and at times conflicting, aims. Tanya weaves the two together in an effortless manner, allowing the reader to consider the process and motivations of historical research, as well as enjoying and learning from the fruits of such research. Tanya has an easy writing style with a conversational tone that makes this book a joy to read.

Fractured Families makes an important contribution to the historiography of public history. Tanya’s work on the history of the Benevolent Society has resulted not only in this book. She has shared her research in a radio documentary on the history of charity, broadcast by ABC Radio National, and provides research advice and on screen talent for the television history program, Who Do You Think You Are.

In the book Tanya explores the influence of television programs such as Who Do You Think You Are in shaping popular understandings of history methodology. Tanya also demonstrates with her family history collaborators the benefits and excitement of the digital turn of history. The digitisation of sources, establishment of bulletin boards and chat groups, the proliferation of blogs have all encouraged a greater public interest in, access to and collaboration for historical research.

Through the vignettes about the family historians that conclude each chapter, the reader gets to reflect upon the motivations of researchers, the methodology and approach of different researchers, and how we can present history.

For me, one of the interesting outcomes from Tanya’s engagement with family historians is the insights around when people start doing their family history. Tanya reports from her encounters that it is often influenced by the life-cycle, such as a death in the family. Recent audience development research that we have undertaken at the City Council confirms this finding. People reported that they became curious about the past when they had children, moved house to another suburb, or was faced with the loss of a parent or grandparent. This gives historical producers and publishers much food for thought around opportunities for engaging and tapping new audiences.

Family history often destabilises the authority of historians – pulling up the exceptions to the rule, and highlighting the complexities of community and family networks. Tanya demonstrates the benefits of adopting a collaborative approach to research and historical writing. The result is a more intimate and nuanced understanding of our past, while at the same time admitting to the ambiguity of sources and the limits of knowledge (p.239-40).

Tanya concludes Fractured Families by stating: ‘Historians are obliged to use our expertise and skills to educate, entertain and excite others about the past. Family history, as all our historians featured here would insist, is a fantastic place to start (p.252)’

I thoroughly agree. Family history is personal, intriguing and complex and it highlights the networks of family, religion, and business that make up our society.

Congratulations to UNSW Press, the family historians and most especially to the author, Tanya Evans. This is a wonderful contribution to the history of Sydney and colonial NSW, and to our understandings of public history. I commend the book to you all and declare the book launched.

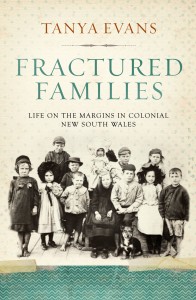

[Photo: Family in a pony cart [with dog] by Mark Brody (c.1905) sourced from – trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/73504942]

How appropriate that this is posted during National Family History Month. I wrote a review of this book at the end of June and despite having written quite a few posts since then, the review has been the most popular post on my blog in the last thirty days. It is attracting a lot of attention on Twitter and Facebook.

This interest in her book is testament to the effort that Tanya Evans has made to work with family historians and her respect for the careful research of the family historians featured in her book.