By Ian Willis

Local studies have an important place in the history landscape in Australia. Local history is incredibly popular amongst thousands of amateur practitioners, yet only a relative handful of academic historians take an interest in it. Both groups appear to have dug themselves into trenches on either side of a no-man’s land of history practice, territory marred by a lack of understanding, trust or desire for compromise. The academic is ensconced in the institutional setting wrapped up in career prospects, peer-reviewed journals and remote conferences. The amateur local historian is unpaid volunteer in a community sector that is under-valued and often invisible. While there is a list of differences between both sides, there is common ground.

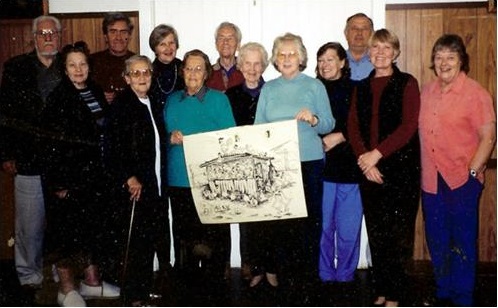

I explored this proposition in my keynote address, ‘Academic snobbery. Local historians need more help’, at the annual Yass Historical Association Conference Beyond the limits of location, held from 8 to 10 March 2013 in the quiet picturesque landscape offered by St Clement’s Retreat and Conference Centre in Galong, NSW. Using two case studies, the Camden’s writers project for the Dictionary of Sydney website and the Wollondilly Heritage Centre History Project, I examined how there can be successful engagement between local historians and academics. Both projects illustrated the development of trust between keen amateurs and academics.

The Camden’s writers project produced 22 short histories for the Dictionary of Sydney website. See also http://www.camdenhistory.org.

I also discussed the principal differences between amateur historians and academics around education and training, issues of authority and expertise, the institutional location of each party, the popularity of local history, the politics of local history methodology and its subject matter. A lack of understanding about each other’s interests and a degree of insecurity stymies dialogue.

Despite these differences both camps share a curiosity about the past. This can produce successful engagement between amateurs and academic historians, built on understanding, tolerance and trust. This will take time. Both sides have much to offer each other and it can lead to a win-win for all parties, as the lively question and answer session after my speech demonstrated.

The PHA (NSW) is in a unique and interesting position with respect this issue. Members have the opportunity, through their work, to start a conversation between amateur and academic historians. They can help overcome the suspicion and lack of trust through open and robust engagement around professional history practice. Such actions will foster greater understanding and a more tolerant local history landscape. Public historians have a foot in both camps and it is in their interests to help bridge the divide.

Thoughtful article. Yes, it’s time to talk about this and much more besides. I suspect that academics have an understandable scepticism about amateurs for all the obvious reasons. And I’ve always found the term ‘Professional Historian’, somewhat difficult and contradictory. I have a view that you can call yourself anything, but the fruit of a historian’s labour should be output in the form of publications. This is where I get in a tangle with those who call themselves ‘Professional’ but have never had anything published. It would be rather like calling oneself a ‘novelist’ on the strength of having written some chapters or have a work in progress. There are far wider issues that I would like to see canvassed, and that is the gulf between those of who work in the corporate/business realm as opposed to taking commissions from publicly-funded institutions. I have always wondered why PHA isn’t better represented among business and/or social and economic histories related to commerce.

I think all parties to this debate need to be a little less precious about their turf. Fewer vested interests and less defensiveness. More openness, a little more patience and less hubris may lead to greater understanding and tolerance. A win for all. This forum and the PHA has an important role to play in this discussion.

This post made me think about what work I do to develop local history. I do some, but not a lot. Then I wondered how I and others could do more and how this could be facilitated.

Perhaps a formal campaign led by historical organisations in NSW such as PHA NSW and the Royal Australian Historical Society could help to address this issue. This could include sharing stories such as this one where trained historians assist local historical societies and providing a forum for local historical societies to make specific requests re certain projects.

I agree with Ron that Ian’s article is very thoughtful and raises topics and much more besides that we need to talk about. In research for my recently published book – Passion Purpose Meaning: Arts Activism in Western Sydney – I was amazed to realise that in all the local histories commissioned by local governments in western Sydney (I hope somehow I’m mistaken), arts and cultural development was almost completely overlooked, or only mentioned in passing. And yet, as my own book demonstrates, it has been the focus of many years of local advocacy and action by a wide range of community groups and strong individuals. While the arts are often about intangible experience like different ways of seeing, crossing cultural divides through shared explorations, opening to new ideas and risk taking, they form a vital “leaven in the lump” of newly forming societies such as those in western Sydney, where new arrivals make their homes every day. It suggests to me that the academic training of historians may be too restrictive.

The professional historian and the amateur who is interested in history can work together. It is an ideal situation where a local historical society can have some input from a professional historian. The historian can give advice and guidance when the society puts together a publication that it should be of a high standard with the sort of features common in academic publications, including an ISB number, index, footnotes, copyright and other acknowledgements, and a bibliography

Katherine you make a very important point. The creative industries an economic driver and often invisible in this context

OK. I really dislike academic snobbery and to return to IW’s point and those made by colleagues in the history chase, I think that we could do more to ‘honour’ the contributions made by so many people in the recording and interpreting of history.

Maybe we need a new approach. Perhaps one of the ‘put offs’ is the rather fusty, old-fashioned baggage surrounding community historians. invariably, they’re retired people with a passion whose exploratory work is absolutely vital in building up a bigger picture. i like it to pointillism in art, whereby the Impressionists built up a remarkable canvas using dabs and daubs, so that when one stands back the entirety can be seen in a different light.

Suggestion: historians, whether in the independent, freelance space that some of us occupy, need to forge links with community. Give illustrated talks on our work, engage, those of us with time and inclination, visit primary schools and work up a simple, appealing program that draws in the grandmas and grandads who have a story to tell.

And top marks to Katherine and her work with new arrivals. I’ve met some remarkable people with remarkable stories, including one spooky series of interviews with a former SS trooper who had met Hitler at a garden party in late 1938. Some people i mention this to respond with amazement, a very small few react as if I had trodden on something smelly …….

In Hampshire, UK, academics and archivists are regarded with respect and affection because of the countless evenings and weekends they sacrifice to support amateur local historians. They accept unpaid posts in local organisations. They run regular free seminars, open to everyone, sometimes with a glass of wine afterwards. They organise bargain-price local history conferences. The University of Winchester co-sponsors an annual local history essay prize with Hampshire Field Club, a prestigious local history society.

Knowledge and opportunities are shared. Hampshire has a long history of publishing academically edited primary sources, making them available to everyone. The Hampshire Field Club newsletter and journal are academically edited publications which enable amateur local historians to have their work published alongside that of professionals.

In return local amateur historians index archives. They help with excavations or process finds. They provide material for the latest Victoria County histories. Comfortable with their amateur status, they are not confined by it. They are open to historical theory and new techniques.

Amateur local historians fare less well in the UK heritage sector, which cannot always distinguish between a volunteer and a serf. But in academia they are treated like royalty.

Sadly I don’t think that Charlotte’s example above is particularly representative of how academic and amateur historians work together. Don’t get me wrong, I am delighted to hear about such close collaboration, but I think that it tends to be rare. That, however, should change as amateur historians often have a wealth of knowledge to share – and so do academics. I would make a plea to my academic colleagues to share more of their work with the wider public rather than sit in their ivory towers.

For historians like me who work in the fields of migration/diaspora history there are ample opportunities for collaboration etc. I love working with genealogists, for example, and their work has substantially supported and facilitated mine. In New Zealand, for instance, genealogists concerned with Scottish heritage have carried out mass data collection projects that academic historians would not have been able to. I hope that my work now is also feeding back to the communities it essentially came from. I think that a lot of positive achievements can come from such collaborations.

as a member of the Writers Group which Ian mentioned in his presentation I can certainly confirm that we grew in confidence and gained a wider perspective through the process.

One very good example of amatuer/professional co-operation is the annual Histroy Conference organised by lorraine stacker on behalf of penrith Council.

It is a living example of upskilling so called amateurs and showing them the respect from professional historians. I go each year and benefit greatly.

Regards

May I remind you that there are many historians who earn their income in universities and who work closely with local historians. Indeed, I’d suggest that my university – the University of New England – with its long record of working with and for local, family and applied history through both teaching (we have awards in the area) and research provides a strong example of where and how academic historians have acknowledged the significance and skills of local historians and all that they do.