Dr Jennifer Debenham is Senior Research Assistant, Centre for the History of Violence and Sessional Academic, History – School of Humanities and Social Science; and the English Language and Foundation Studies Program, University of Newcastle.

Her current area of research is examining the ways in which Aboriginal Australians have been represented on documentary film from 1901 to the present. This study casts light on how social attitudes and politics have affected approaches to Aboriginal peoples.

What made you decide to pursue a career in history?

I came to a career in history by accident. I enrolled in a university enabling program where Australian history was one of the options. I had enjoyed history when I was at school but history at university was very different ―and I developed a passion. My success at university led to post-graduate studies and to teaching, something I had never dreamed of doing. Working on research projects has been rewarding. I am always amazed by the people I am fortunate enough to meet. I love discovering what motivates people, given they exist in a particular social and political environment. And I love the detective process of finding a particular bit of information that contributes to my understanding of our society.

Who is the audience for your history?

Parts of my work are aimed at an academic audience because I am a member of that community. But I like to be able to change my writing style to suit a wider public audience. I want my audiences to be infected by my passion to understand our past. There are so many fascinating details about Australian history that appear to be unappreciated; so it is my job as an historian to address my research to a number of different types of audiences. It is important to keep history relevant by understanding current developments so that we are able to address the public’s interests. These were considerations when I worked with Christine Cheater on The Australia Day Regatta (UNSW Press, 2014), a history of this annual sporting tradition.

What is your favourite historical source, book, website or film?

This is a very difficult question to answer. I love going to the journal databases but there is something alluring in the tactile relationship you develop with original documents and artefacts. The smells and the textures make you think about the people who produced them. The stimulation of these senses makes you ask questions about the author and what they were thinking at the time. On one occasion, I examined the field journals of Felton Mathews in the NSW State Library. Studying the drawings he made and looking closely at how the lines composed an image made me think about where he was sitting, who was with him at the time (and even if he had enjoyed his breakfast!). What inner spiritual reaction did he have when he looked over those heavily wooded ranges to record them in his journal? Artefacts are the things left behind by people who laughed, cried, developed ambitions and jealousies – the material existence of a person is represented by one small fragment of their lives; it can tell you so little and yet so much about a person―that is fascinating to me.

If you had a time machine, where would you go?

What a choice! The medieval period has a certain appeal. Often when this term is used our minds go to Europe but I think it would be fascinating to visit other parts of the globe such as Meso-America and the Middle East. It would be good to talk to philosophers and academics about some of the ideas they were developing in the arts and sciences and how they rationalised the world they inhabited. A trip to Australia would be fantastic to see the social and political structures of Aboriginal peoples and how they traded, lived and socialised with each other. How different the map of their nations would look! And it would be amazing to find out what, if any, other languages were being spoken.

Why is history important today?

History is important today because it illuminates the events and the reactions to those events that helped form a national identity. Identity is just as important to a nation as it is to an individual. It’s important to understand why some events, such as the myth of Gallipoli, command such an important aspect of our history. What happened to make it so and why do we keep up the narrative of uncommon valour as being a uniquely Australian attribute? Historians are often pilloried for their scepticism and ‘lefty’ analysis but it is the historian’s job to be critical and analyse the narrative of the nation. Of course this is affected by the present and the context in which we are writing and researching; fifty years ago the valour of Anzacs was ‘common sense’ and was rarely questioned by historians or the public. Recent research into psychology, as well as new understandings of post-traumatic stress disorder of war, have recently altered the way we think about soldiers’ experience.

I think history is understood by many people as something in the past that cannot be changed. That is far from the truth. Our understanding of past events is flavoured by the present. Present historical understandings have altered the ways in which the motives and actions of historical protagonists are being examined, shifting us to new interpretations. History is important today because it is an active debate or conversation we continue to have with ourselves, as a nation and as individuals; it helps us understand the whys and wherefores of our existence.

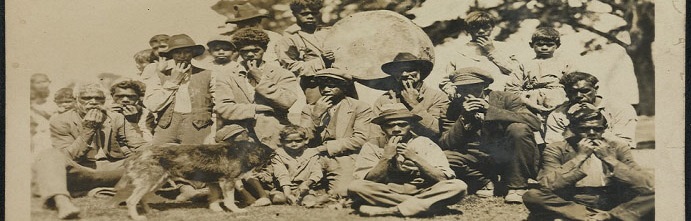

Image: Recto of Gum leaf Band at Lake Tyers, Victoria Part of Jim Davidson Australian postcard collection, 1880-1980. nla.gov.au/nla.pic-vn6448949-s1

What an interesting profile demonstrating once again the exciting range of work our members do Jennifer, next time we meet let’s debate your comment ‘fifty years ago the valour of Anzacs was ‘common sense’ and was rarely questioned by historians or the public’ which I question. It is 50 years since Australia first started our disastrous escapade in Vietnam and as a result many Australians robustly questioned our participation in not just this but in earlier wars as well – with the exception of the fight against the Japanese in WWII. Also I haven’t researched attitudes to WWI veterans in the inter-war years but I suspect there was scant veneration for them at that time. My perception is that no one cared too much about them until they were nearly all dead! Then few listened to the words of the last survivors which were generally along the theme of ‘war is hell, don’t glorify it’. Just some random thoughts.

Hi Pauline, thanks for your encouraging remarks. Yes maybe I was a bit flagrant with my time line I’m forgetting to add more years as I get older! I was thinking about the hidden violence done to soldiers and their “duty” to look like they had weathered the war well. This feeds into the ‘heroic’ mythology that surrounds Anzac. It is an area that is attracting more attention as we critique the Anzac legend in more ways. This is seen as an unpatriotic slur by some commentators but we need to be continually questioning the construction of the legend and the purposes it is used.